Marcus Nunes has a great new post that expands on the three main points of the phenomenon of the Great Stagnation made by Scott Sumner in rebuttal to Krugman/Summers. He provides an explanation of those points, including graphical representation of the theme, pointing to ineffective monetary policy as a primary root cause.

The points from Sumner are:

It seems to me that the Krugman/Summers view has big problems:

The standard textbook model says demand shocks have cyclical effects, and that after wages and prices adjust the economy self-corrects back to the natural rate after a few years. Even if it takes 10 years, it would not explain the longer-term stagnation that they believe is occurring.

Krugman might respond to the first point by saying we should dump the new Keynesian model and go back to the old Keynesian unemployment equilibrium model. But even that won’t work, as the old Keynesian model used unemployment as the mechanism for the transmission of demand shocks to low output. If you showed Keynes the US unemployment data since 2009, with the unemployment rate dropping from 10% to 6.1%, he would have assumed that we had had fast growth. If you then told him RGDP growth had averaged just over 2%, he would have had no explanation. That’s a supply-side problem. And it’s even worse in Britain, where job growth has been stronger than in the US, and RGDP growth has been weaker. The eurozone also suffers from this problem.

The truth is that we have three problems:

A demand-side (unemployment) problem that was severe in 2009, and (in the US) has been gradually improving since.

Slow growth in the working-age population.

Supply-side problems ranging from increasing worker disability to slower productivity growth

To which Nunes posits:

I posit that the demand shock was so severe (and long lasting) that it greatly helped mess up the supply side. That means that now, the previous level of activity is not attainable (at least for a long time). The charts indicate that all those supply side factors went “off” after the “Great(demand shock)Recession” hit, a consequence of the Fed´s (and many other central banks) “Great Monetary Policy Mistake” of 2008.

The next chart indicates that the economy, even given the supply side “negatives”, could be at a higher level of activity. Closing a $1.7 trillion gap through, say, an NGDP Level Target not allowing all bygones be bygones would also do “wonders” for the supply side!

Sumner’s is a great analysis of the Krugman/Sumners view of the phenomenon of the Great Stagnation. But, in my view, it is a very high, forest-level view on the side of too simplistic for the following reasons:

One might assume from the narrative that there was a single demand shock from which the economy could naturally heal and I do not believe that to be the case. In other words, if one were assume a certain level activity to be occurring in 2007-08, then the demand shock occurred in 2008, a crisis ensued and we worked through it, the assumption that what we have now is purely supply side, I think, would be appropriate and probably accurate.

But it misses some facts, as it leaves out the subsequent demand shocks in 2010 and again in 2011. The US did not experience an official double-dip, but that doesn’t mean that economic conditions did not go from bad to worse. Additionally, the US doesn’t exist in a bubble, and the ECB was raising short term nominal rates in 2011 against the backdrop of the Fed’s 2% PCE ceiling. Therefore, the expectation that the US economy can recover from multiple negative nominal shocks spaced over a period of three years to be anywhere near “normal” by now else it’s a supply side problem is likely only partially accurate only two to three years after the nominal shocks have subsided.

My elements of contention are these:

If you showed Keynes the US unemployment data since 2009, with the unemployment rate dropping from 10% to 6.1%, he would have assumed that we had had fast growth. If you then told him RGDP growth had averaged just over 2%, he would have had no explanation. That’s a supply-side problem. And it’s even worse in Britain, where job growth has been stronger than in the US, and RGDP growth has been weaker. The eurozone also suffers from this problem.

I don’t particularly follow this point because in addition to employment growth being stronger and RGDP being weaker in the UK, inflation has generally been running stronger than the target. That does not appear to be true in the EZ or in the US.

Bernanke said that the way to determine the stance of monetary policy is to consider both NGDP and inflation. Monetary stimulus applied on top of an inefficient supply side tends to lower unemployment and raise inflation. So I agree the UK probably does have more supply side problems than monetary problems. But elevated inflation doesn’t appear to be a problem in the EZ or the US, which have yet different problems.

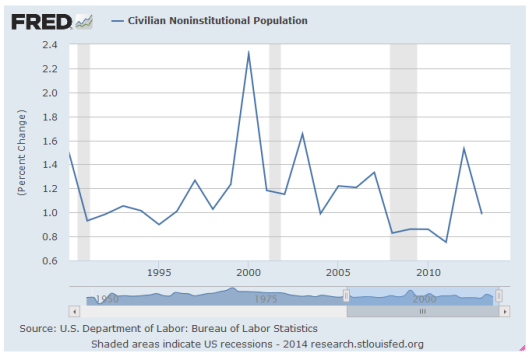

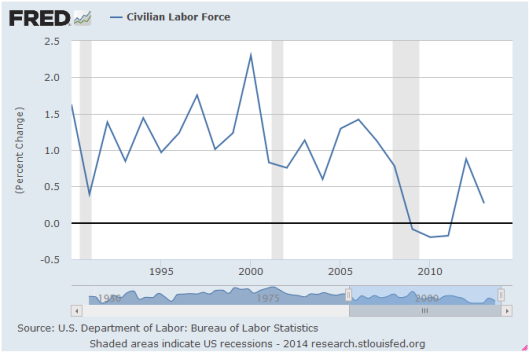

Slow growth in the working-age population.

I might be wrong, but I don’t see it. I see declining LFPR, but no noticeable slowing of growth in the population of non-institutional civilians over the age of 16 that wouldn’t have had apparent effects different from the mid-1990’s starting in 2005. Perhaps monetary policymakers were competent in the mid-1990’s?

It also worth noting that civilian population growth disappears right before a recession officially begins – immigrants go home or domestic citizens head for greener pastures?

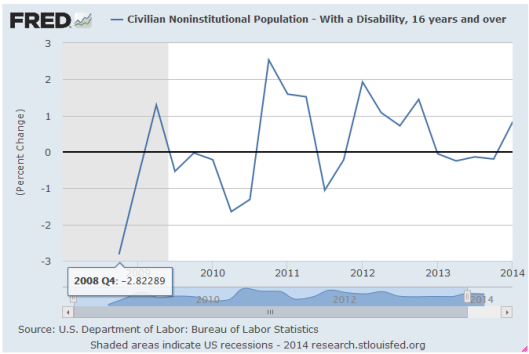

Supply-side problems ranging from increasing worker disability to slower productivity growth

This probably needs more research because the statistics on FRED for growth in the disabled civilian population over age 16 is available only since June of 2008, and there isn’t anything to compare with other recessions. But it does appear to be the case that there has been growth in disability while in June of 2008, it had been shrinking.

My point of confusion here is whether this is indicative of what could be considered an extension of UI given the decline in LFPR with no noticeable decline in population growth that could be rolled back with appropriate monetary policy. An increase of actual disability, people with heart problems or physical handicaps is a supply side problem. An increase in fraud in the disability program is a supply side problem. An increase in people creating their own extensions of UI by claiming pseudo physical or mental ailments to get into the disability program due to a need for survival combined with a lack of available productive endeavors is most likely not a supply side problem, but rather an extension of a persistent cyclical unemployment problem.

It’s impossible to disentangle available data in order to be reasonably sure which problem we have. Thus this point is easy to state, but harder provide conclusive evidence. One would have to believe that the US experienced a sudden breakout of disabling health problems that coincided with the most impactful nominal shock in generations; a point that is questionable at best.

My overall suspicion is that in the US, the main problem is still mostly nominal with supply side disincentives such as lax fraud enforcement in the disability program that reduces the incentive to work, which is likely some portion of low LFPR. It may be solvable in large portion by solving the nominal problem, making the incentive to work greater than the disability disincentive to not work.

Cracking down on fraud in the disability program without addressing the nominal problem is not a plan I would endorse. And the reason I wouldn’t endorse it is at least one reason, that we can’t just start cutting people off of the only life line they have without having provided enough opportunities in the economy so that they may find some other means of survival, I think some revision of the argument is needed. Assuming that by now all of the problems are on the supply side, or even mostly on the supply side, it’s hard to tell exactly what is being claimed, doesn’t contribute much to solving the crop of problems.

Benjamin Cole said:

Goof blogging.

I agree—I would be a little happier if i knew we were kicking people off of disability and welfare into a roaring job market.

But when there is not enough jobs, what do we say to people? “You are a loser,” does not seem productive.

TravisV said:

Bonnie,

This post is extraordinary–one of your absolute best that I’ve read (and I’ve read a lot of them).

Millions of people who were fully-employed in 2007 are underemployed now, and that isn’t by choice. It’s due to lack of demand.

The top two blog posts of September 2014: this one and Nick Rowe’s on the Inflation Fallacy:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2014/09/its-the-inflation-fallacy-duh.html

dajeeps said:

Travis and Ben, thanks for stopping by. This was actually two blog posts that I stuffed into one rather hurriedly. I wish I had more time to spend on blogging in order to make my points clear. But alas, I can’t quit my day job. I am glad you were able to understand my point. 🙂